Interview: Poet Camille Martin on ‘Looms’

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

The scholar John Rodden calls the literary interview a “fully-fledged genre.” I used to be skeptical, but after assigning my students at The College of Saint Rose to speak with an author, I’m more inclined to think the literary interview qualifies as a distinct form of performance. I put out a call on Facebook and Twitter: Would you speak to a college student about your book? I asked. Sure, they said. Review copies were sent, students selected authors, read and researched their work, and asked questions. - Daniel Nester, Contributing Word Editor |

POET CAMILLE MARTIN ON ‘LOOMS’ |

||||

INTERVIEWED BY

|

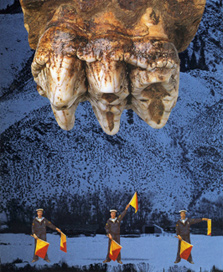

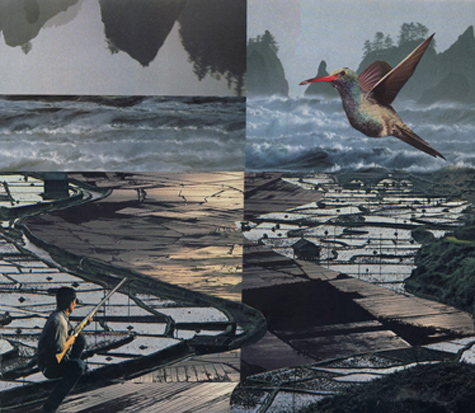

Poet, collage artist, and classical pianist Camille Martin spent her childhood and early adult years in Louisiana. She currently resides in Toronto, Canada. Ms. Martin is the author of four full-length poetry collections: Sesame Kiosk, Codes of Public Sleep, Sonnets, and her latest release, Looms. Her training as a musician gives her poetry a unique flavor. She feels there is definitely a connection between language and music and says that when she writes poetry, she is “aware of trying to make the language sing.” Camille writes “for the sheer joy and pleasure of the sounds of poetic language”. In an interview conducted over several email exchanges from her home in Canada, we discussed what the word “looms” means to her and her training as a classical musician. ROSENTHAL: Looms are tools for weaving threads into tapestries. Looms can also mean the imminent arrival of something just out of sight. What does the term “looms” represent to you? Why did you choose this title for your collection of poems? MARTIN: In Looms I began to write narratives that wove together disparate strands that still somehow blended within the poem’s tapestry. I liked the double meaning of the word “looms,” which suggests the possibility for expanding meanings. That double-ness makes me curious about how the two meanings of “looms” might relate. In a similar way, weaving together in one poem images from different realms—the altitude of the moon and a tightrope walker, for example—might cause a reader to wonder how they relate. And the thought process of the reader is part of the poem, too! ROSENTHAL: You were trained as a classical musician. In what ways does your musical background influence or contribute to your poetic style of writing? MARTIN: To me, language and music are closely related. Even ordinary speech is musical: think of the way your voice makes a melody with rhythm as you talk. A musician could even notate ordinary speech as music—and in fact many songwriters and opera composers pay close attention to speech accents, inflections, and rhythms. When I write poetry, on some level I’m aware of trying to make the language sing. ROSENTHAL: You have been described as both a visual artist and a collage artist? Is there a particular genre of visual arts that appeals to you most? MARTIN: As a visual artist, I work primarily in collage. I like the way an object is transformed when it’s juxtaposed with another object—for example ancient fossils and semaphore flags. |

||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| (“At Peril”) | |||||

|

When confronted with such a juxtaposition, the human mind does what it does best: try to figure out what one might have to do with the other. A narrative might begin to take shape, or maybe a philosophical idea. Another possibility is to allow the two things to stand without trying to bridge the gap—to simply enjoy the work’s strange or playful qualities. ROSENTHAL: You have said that the “woven tales” within Looms are “like parables with infinitely deferred lessons”. What lessons would you like the reader to take away from your book? MARTIN: My favorite poems don’t so much convey lessons—“morals of the story” or nuggets of truth—as possibilities. I read in order to think, to follow the ripples of meaning that expand from a word, phrase, or sentence in the poem, and to see how one thought leads to the next. And I read for the pleasure of poetic language: its patterns and surprises of sound, image, and idea. And I’m also aware of the emotions that I experience while I read poetry. ROSENTHAL: Can you tell me more about your poem, “They will take my island”? Who or what exactly does “they” refer to? MARTIN: That poem was commissioned by a poet friend, Paul Vermeersch. He asked several poets to write a poem beginning with the words, “They will take my island,” which is the title of a painting by Arshile Gorky. Beyond the first line, the poets had complete freedom to write what they wished, and to interpret “they” in their own way. In my poem, I never offer a fixed identity for “they,” so that readers might play with their own interpretations. ROSENTHAL: What significance does the last line in your poem beginning, “Where peasants now hack at tough clods,” have? Does a blue banner with a crescent moon have an underlying meaning? MARTIN: The particular color and emblem of the banner don’t have symbolic significance for me. For the purposes of the poem, I was thinking of what might be on the flag of a medieval kingdom, and the crescent moon appears on heraldry, coins, and flags in many different cultures, throughout history. ROSENTHAL: Can you explain some of your thoughts surrounding “Nostalgia came later”? I was particularly struck by “We deduce that who we are depends on how we ask the question and who asks it” and “whispering a rumor isn’t the same as inheriting it”. MARTIN: In this poem I was thinking about evolution and the question of nurture/nature: to what extent are we the result of traits inherited from distant evolutionary ancestors, versus traits that we’ve acquired through experience? Who are we and why? I don’t think that our human qualities can be entirely explained by evolution—for example, the self-conscious thought that you quote from the poem, problematizing the question of who we are. On the other hand, human behaviors such as tribalism (the “guarded terror of the other”) likely result from our evolution. Readers might interpret the poem in different ways, but this is what I was thinking while writing it. ROSENTHAL: Does your poetry usually begin as a single thought or phrase in your mind that you want to further explore, or does it begin more as a collection of thoughts or ideas? MARTIN: That’s a very good question. Sometimes a poem begins as a single idea. An example: I took a walk to Sugar Beach on Lake Ontario—so-called because of the view of a nearby sugar refinery. I began the poem as a description of the scene, from the white sand to the raw sugar transferred by crane from a barge to the refinery. I wasn’t sure where the poem was going. As the poem progressed, it became something more complex: a meditation on the nature of memory. I was fascinated by Sugar Beach triggering a distant memory and the associations my mind was making in the process. Other times, I deliberately juxtapose images to see what thoughts might ensue: flooding streets and a Viennese operetta, for example. Either way, when I set out to write a poem, I can’t necessarily predict the direction of the poem, which often seems to have a mind of its own. |

|||||

|

Visit Camille Martin… |

|||||

Stated

Stated

Reader Comments