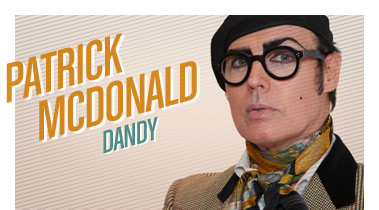

Patrick McDonald: The Dandy of New York City

(Photo: Thomas V. Hartmann)

A “Dandy” is a man who places the highest of importance on physical appearance and manner. At the velvet ropes of Studio 54 at its peak in the 1980’s, there was little more important than physical appearance, and there were very few as confident as Patrick McDonald, “The Dandy of New York.”

Moving to New York City in the late 1970’s after graduating from Pepperdine University, a relatively conservative and religious university in Southern California, a young Patrick was determined to live among the celebrities, artists, socialites, and freaks he saw in the pages of Warhol’s Interview magazine. “I belong there,” he said. “These are the people I need to be around.”

However, according to photographer and artist Molua Muldown, whose friendship with Patrick traces back to their clubbing years of the 80’s and 90’s, his people are now an “endangered tribe.” The two began symbolically documenting the tribe, photographing Patrick among some of the New York landmarks that have also begun to disappear.

Molua and Patrick’s collaboration with artist Lisa Pan on the photographic series, “The Dandy’s New York” at the East Village’s Dorian Grey Gallery, tells a story of landmarks and locales throughout New York that represent a time when young artists and dreamers would come to the city year after year, bringing with them fresh creative energy and idealism. The series closes the chapter on a Manhattan that is no longer the property of the fabulous, but the fabulously wealthy.

We joined Patrick, Molua, and Lisa in the East Village for a conversation about the show and about their New York City.

stated: Let’s start by talking about the show, about the concept behind the show and when it began. I understand from walking through the show with Molua that it really began before the concept was in place, yes?

Molua: It kind of did. We had a really loose idea in 2001 that sprang from me knowing Patrick for many years and seeing other artists, painters, illustrators, and photographers using him as a muse, but not really getting below the surface in my opinion. So I wanted to reveal the man behind that façade, in a more intimate way.

So we began. We had these feelings even in 2001 that our city and our landscape were embarking on this really rapid process of change. And some of it, like all evolution, is good and some of it broke our hearts because we saw some of our landmarks and some of our favorite spots shrinking and disappearing and that meant that some of the people that were in our little honeycomb of a hive were also disappearing.

So we started in the flower market, which at that point was still the flower market as we used to know it, but we could see that it was being encroached upon and shrinking; we started there.

(Photo: Molua Muldown, 11 x 17 C-Print ) (Photo: Molua Muldown, 11 x 17 C-Print ) |

The Flower Market, 2001 Perhaps he thinks that I didn’t see him as he stepped inside the passing crowd But sometimes it’s enough to keep your own counsel, be your own man - Patrick McDonald |

Patrick: We started there and where did we go after that?

Molua: Patrick and I would meet frequently at Life Cafe, which no longer exists. We used to call it our office; it was on 10th Street and Avenue B. So we would conspire about all the things that were changing, and all the things that we love, and where we should go next. We did a little tour of the East Village and of the mosaic trail there.

Patrick: We also went into CBGB’s to photograph. I was actually a big part of the night scene in New York for years. A little less now than I used to be, but a little heavy duty at one time.

Before I lived in the East Village, I lived in Chelsea and I lived next door to the Chelsea Hotel, in a building called the Carteret. And we photographed me in the Chelsea because for many years I had friends in the Chelsea and have been to a lot of wild parties there ever since I came to New York in the late 70’s.

I grew up in California and Molua grew up in California. Actually we met in the 80’s at Barney’s downtown. We both worked at Barney’s. And it was different in New York then, the scene was different. It was just coming off the Studio 54 era and I moved to New York during that time in the late 70’s. But the scene was moving downtown. And that’s when Barney’s became a known destination. Even though it had been a store for years at 17th [Street] and 7th Ave, it became this luxury department store that people went to. And the whole club scene popped up in that neighborhood with Area and Nell’s and the Limelight.

And Molua and I, that’s where we became friends. We had the same sensibility, and when I moved to the East Village, and even before the East Village that’s when we began this collaboration together.

It’s been fun, it’s been organic. Like the shots in Chinatown. Let’s do Chinatown! Ok, I love Chinatown. Chinatown going to Wo Hop at 4 or 5 in the morning after a wild night out, climbing down those stairs. Heaven knows I would not eat any of the food I ate at 5 in the morning now, or even then if I really saw what it looked like.

But I think Molua captured the spirit of New York during this 10-year time period. Especially the Chelsea Hotel pictures and CBGB’s on stage. Molua and I had permission to go in there with no one there and take pictures in the infamous bathroom downstairs and the stage upstairs and those are treasures that we are losing in New York. I mean, John Varvatos opened a store there and he preserved some of the walls for you to see, but it’s not what it was, it’s just not what it was. I mean, how many times did I go visit friends of mine on Bleecker Street and you see from a distance that ratty CBGB’s awning that you were so used to seeing all the time? And then it’s gone.

|

|

Molua: But we were very lucky. Most people we approached in these locations are real fans of Patrick. He has a real following. They were very, very open to us when they discovered what we were going to do, that it was our intent to preserve something. So we got permission from a lot of spots that ordinarily you would think we would not get permission from. For example, Jimmy Webb, who runs Trash and Vaudeville. I had known Jimmy for a few years, and when I wanted to photograph Patrick there I knew somehow that both of them would have an affinity for one another. They are both, in a sense, members of the same endangered tribe.

And this is when the collaboration began with Lisa’s work, in that image, it seemed to me that it could go further than it had and since I wanted this project to be as authentic technically as possible, I only used real film and only my hands in developing and printing the photographs. It was really important for me to keep that artisan aspect of it as much as we all hate that word now. This is where Lisa came in and started doing hand painting on top of the photography. We started working on a deeper manipulation of the work as it evolved and we started painting on top of other pieces that we are calling our artists samples, and collage work and intensive razor cutting and layering.

This [project] was our real labor of love we intended. New Yorkers have *their* New York, and they might tell their friends that come from out of town, “Let me show you the New York that I know.” This was the New York that we knew, and we didn’t know at the time that we began this that it would be part love letter and part eulogy.

stated: You speak of an “endangered tribe.” What’s happening now that you feel is similar to what you guys found when you arrived in the early late 70’s and early 80’s? What is the new tribe?

Molua: I think it’s a dilution of the roughage. I think everyone we know would agree with that. Everything in life is a cycle. There’s always evolution and that’s undeniable. But the reasons that people like Patrick and I and Lisa came here, and the reasons we stayed here, was this [New York] has been a magnet for those who were outsiders wherever they came from, or for those looking to follow in the footsteps of the ghosts that came before them. Today, we even have people like Patti Smith telling artists New York is over; it’s been taken away from you. I certainly feel like there’s an element of truth to that. We feel like those ghosts are still here and there’s always hope.

Patrick: I feel like New York has been scrubbed clean of the creativity. And the people that have scrubbed it clean feel like it’s a gritty part of New York and they don’t want to have it anymore. And it’s not a gritty part of New York. It’s what makes New York New York. I find that the whole idea of doing away with the Chelsea Hotel, and CB’s and those places because of greed in this city is ridiculous. But you know what? The people that are pulling the purse strings, that are running New York, they don’t care. They don’t care. You know they don’t. But it could do a turnaround. It could. I hope it does.

Molua: It’s a time of really intensive mourning and heartbreak for all of us who feel there are footsteps we could be maintaining here. With every building that is knocked down the ghosts that are knocked down with it. I think of all the times that we walked these streets and said to one another, “You can almost hear those footsteps, this is where my favorite writer lived, this is where this incredible painter lived,” or “Do you know you are standing outside of William Boroughs’ bunker when you stand here?” Those things give you a thrill in a certain way, and inspire a kind of courage for anyone pursuing the difficulty of leading a creative life, and presenting themselves as an unconventional artist.

|

|

stated: Patrick, when were you first referred to as the “Dandy?”

Patrick: Hmm…I’ve been referred to as many other things. (Laughter) In the 80’s. A “dandy gentleman.” Or, “well-mannered like a dandy.” But when I heard the word “Dandy” for the first time was when I was a little boy and I watched James Cagney in Yankee Doodle Dandy, and I was mesmerized by his fancy footwork on stage, the fabulous way he dressed. But I think I always knew of the Dandy as Mr. Peanut. (Laughter). He was a true Dandy.

stated: With his cane and his hat. Always the gentleman.

Patrick: But you know, in New York, I used to see Quintin Crisp around the East Village and he was the ultimate Dandy to me. Besides Oscar Wilde. But someone who was actually living was Quintin. I felt an affinity for Quintin and we talked and we knew each other and I felt that I was really related to Quintin in a Dandy way.

stated: Was there ever a time when you had a circle of friends who dress like you dress? The present themselves, carry themselves like you do?

Patrick: No one dresses like me! (Laughter). They dress the way they dress, and I love the way they dress. But they’re different. We all are our own creation. That’s why they’re my friends.

stated: I like Molua’s photograph of you at the Mermaid Parade on Coney Island, where you seem to be dressed in more civilian clothes. It was hard to find you in that photo!

Patrick: It was appropriate; I was taking the train. I was going to Coney Island. I had never been to Coney Island. I’d been there to a party in the late 70’s, but I don’t remember how I even got there. But I have to say that it depends on the day. I don’t know if I’d call those civilian clothes! I had a fancy scarf on my neck. And a fancy pair of sunglasses on, actually. But someone still found me and photographed me that day and put me in a newspaper.

stated: You seem to have the license to do anything you would like. You don’t need a parade to have that freedom.

Patrick: No! You don’t need a parade. But I do believe in respect. For instance, I travelled to Istanbul with a dear friend of mine. And I didn’t go like this to Istanbul. I didn’t want to be killed. I wanted to have respect for the culture there. You know, I still snuck in a silver pair of shoes. But I didn’t do a full face of makeup to walk into the grand bazaar because that wasn’t going to fly there. And I didn’t want to go to jail either.

stated: Well, that would be quite a story.

Patrick: No it wouldn’t be! It would be a saaaad story. A tragic, sad story.

Molua: We don’t want him to resemble Quintin Crisp to that extent.

Patrick: I moved to New York so I could feel the freedom that I could do what I wanted to do. And I still think it’s a city for that. But people are getting more afraid, because it’s becoming a city of everybody being the same or wanting the same thing. And I think that if Molua’s work, and my poetry can be an example to someone that’s afraid to step over the line a little bit, then that’s important. We’re losing the characters of New York. Colette came to the reading today and she is a character and an amazing artists.

(Photo: Thomas V. Hartmann)

But you know, the Quintin’s and the Klaus Nomi’s — there aren’t as many because they’re not accepted as much. Because they’re poor. And they’re creative.

stated: So you feel that it’s no longer acceptable to be a struggling creative in New York City?

Patrick: Definitely not. It’s not acceptable. It’s not affordable.

stated: It’s not affordable, but is it not culturally acceptable?

Patrick: For the culture that’s running New York it’s not acceptable. They don’t care. They don’t get it. They don’t want to get it. They are wearing blinders. And they should be hooked up to the carriages in Central Park and rode around.

Molua: The example of Patrick—for anyone leading a creative life—it gives them great courage. You know, a lot of people I speak to or know that I’m doing this project with Patrick, no matter how bad the day is, if I walk down the street and see a purple scarf and a green jacket and a hat and all of these colors and patterns and scale, so exquisitely put together in an unexpected and courageous way. If he can walk around like that and be an example for all of us, then we can all have courage. It’s in a way I’m sure unintended, but it’s the eventual outcome set by Patrick.

Patrick: I’m pleased by that, but I just wish there would be more people taking the step. I feel like there are less people taking the step. I have people say to me, “I wish I could dress like you.” Well, I don’t think you should dress like me, I think you should dress the way you feel. If you feel you want to wear a purple hat instead of a black hat, then wear the purple hat. Just wear the purple hat. Just wear it. What are you afraid of?

Maula: It’s a conformity issue and not everyone is brave enough to take a stand against conformity.

stated: Patrick, you are referred to as a muse. Can we talk about some of the professional work you’ve done? I know you were recently in a film about Bill Cunningham.

Patrick: I was asked to be in a film called Bill Cunningham New York. And how that came about, they asked me because I’m probably the most photographed man he’s had in the paper [The New York Times]. I had a whole page once, and one year I was in 50 weeks, and Bill gets me. He’s wonderful. But that’s not something I’ve done, that’s just something I was a part of and it was an honor to be a part of that, and to be a part of his legacy.

But what do I do? I try to survive every day in New York. That’s what I try to do. I try to be happy. But I’ve worked in fashion for many years. And I’ve worked for some fantastic, marvelous designers from Fabrice [Simon] to John Anthony, for many, many years doing everything with them from PR to trunk shows, from Palm Beach to London. But at the moment I’m freelance. Freelance, I love that word. “Freelance” means I’m just broke!

Maula: Designers go to him as a collaborator because there are very few people that have that adventurous sense for color and scale and pattern and that’s a critical eye that’s hard to find.

Patrick: I still keep my hand in the night scene. Not so much, because I don’t like to stay out so late, but I do have my hand in it because I do host things for fun. There are some fantastic people in New York still. Paisley Dalton is an amazing DJ. Or Joey Arias is an amazing performance artist here in New York. So if I’m asked to host something involved with my friends, I definitely do that, because it’s a chance for us to be together. It’s that shot in the arm that I need. When I moved to New York, that’s really when I grew up. So when I have the opportunity to be in a room with all the creative people that you grew up with, we can learn from each other and support each other, because we are a small circle.

stated: What was it like when you arrived in New York the first time, when you got off the plane?

Patrick: I heard the “Theme from Mahogany.” “Do you know, where you’re going to?” I moved to New York with a girl named Snoogie Brown. I met her in college. We moved to an apartment that was her father’s for a brief moment. Central Park West, The Eldorado. I got a job at Fiorucci’s [ clothing store ] and it was like a club during the day. That’s where I met Joey Arias, Klaus Nomi, Antonio Lopez, everybody. Everybody walked through the doors of Ferrucci during the late 70’s. And my roommate Snoogie got a job working at Studio 54 as Steve Rubbell’s secretary. Not for a long time though, because she didn’t believe in working very hard. It was Ferrucci by day, Studio 54 by night. Every day. EVERY day. I’m not joking. Every day.

stated: What was it like prior to moving here?

Patrick: I went to Pepperdine in Malibu. It was fantastic. I was wearing my elephant bell-bottoms into West Hollywood going to Studio 1. My friend Gordon and I were stalking Andy Warhol when he was in town, or following Rod Stewart. Just getting into the club scene. The Whiskey on Sunset, or the Odyssey. It was the heyday of disco. But the minute I graduated from college I knew I was coming to New York. I knew because my mother took Interview Magazine when it was a fold-over newspaper. Even before I started college, I would look at it and see the sketches by Antonio Lopez and photos of Jerry Hall, Mick Jigger, Pat Cleveland, who I’m a friend with now. But I’d see these people and I’d say, “I belong there, these are the people I need to be around.” It was glamorous, it was exciting, and there were men that were flamboyant, that were part of the inner circle of New York City. I got on a plane about a week after graduation from college and I stayed.

stated: Do you think that dream doesn’t exist anymore?

Patrick: It doesn’t exist.

stated: People still move here with that in mind.

Patrick: But it’s prohibitive. I moved here with $100. I lived with a friend and we got an apartment. I worked at Ferrucci and made $125 a week. And for $125 a week I could afford my rent, I could afford a slice of pizza for lunch, and a soda for twenty-five cents. I could afford my token to get around the city and I was out every night, living on $500 a month. Which was very little money. My rent was $100. It was what they always used to say, your rent should be 1/4 of what you make. And it was. But now it’s not. Because rent now for studio apartments can be $3500/month. So 1/4 of that is $150,000 per year. Who makes $150,000 a year when they first move to New York after college, especially in fashion? They want to give you $12/hour.

Woooo, I’m on a soapbox! I’m on my dandy soapbox! It’s disgusting. And they want people to intern for nothing! There were no interns when you were 18 or 19. You got a job. And now you can’t get a job because you’ve never had a job before, even though you went to college and they put you through the rigmarole of 150 interviews to sell a pair of jeans?

Molua: It’s very sad. So you don’t find those crews of people arriving every year anymore.

Patrick: They don’t come here.

Molua: They can’t. Or Patti Smith might be right: this is not a city to draw the outsiders or creative thinkers. It’s just prohibitive.

Patrick: They can’t even go to Williamsburg. It’s too expensive. So where’s it going to be? Buffalo, and you can commute to the city.

stated: Many of the artists we speak to at stated are nowhere. They are completely mobile. They are bouncing from city to city, month to month, and that’s the intent.

Patrick: I think that’s sort of interesting, though. I think that’s great.

Molua: It’s interesting but you really can’t develop what’s required to make an art movement, which is collaboration, competition, and camaraderie; those who love and hate different things. These require face-to-face relationships and face-to-face work. I think it’s very sad and of course I’m sure the people that are bouncing from spot to spot would prefer not to be. It’s a matter of necessity.

stated: Well, they have to stop at some point, so that’s when things might get more difficult. But a lot of the movement is based upon collaboration, so someone comes up with an idea, and a bunch of artists come together for a month or some period of time and live in small shared spaces, and they collaborate. So there is an unsettled component to it, but they are producing art while moving from spot to spot.

Patrick: And they can’t afford to come here. I remember coming to New York thinking where are we going to get an apartment. I lived on the Upper East Side. There were prohibitive places then. I wasn’t going to live on Fifth Ave. I just knew that. And if I couldn’t afford to live where I lived then, and a lot of my friends couldn’t. They lived here in the East Village and it was dangerous. They were paying $50 a month for rent. Now you can’t name one place in New York—in the city itself—where you can get a place for reasonable rent. You can’t. And there are kids that are living here, but they are living four people in a studio. It’s disgusting.

stated: We are living through it right now. What affect is this going to have?

Molua: It’s stunting and handicapping. What would organically be happening in any other era, in which people would be developing the new, the next thought forward and not just in the visual arts. You have musicians, painters, photographers, and dancers…everybody thinking and feeding through a cycle to create the new.

Patrick: For me, in New York everything comes from the streets. So to be in New York for two weeks or a month, you aren’t going to get from New York what you could in that short of time. Where’s the focus? I love the vagabond idea. It’s interesting and I think it’s great, but still, you don’t have the time to take it from the streets. I think that the travel, the caravan, is because of survival.

Molua: Being poor takes a lot of time and so does the ability to get stimulation with collaborators. If all of your time is taken up to avoid being poverty stricken rather than just poor, you’re really not getting that stimulation of just walking down the block and looking and seeing Jimmy’s Tattoos and being able to focus on, “Why is that person putting an Iggy quote on his back? What does that mean to him?”

Patrick: And thank God I’m old already. I thank God every day that I was able to come to New York when I came to New York. I feel lucky and blessed to walk the streets and still see some of the artists are around.

A few months ago, it was a snowy night. I’m headed towards Bowery and past Pat Field’s store. It was late. And it’s the corner of Bowery and Houston, and I see on the corner this cherry picker and someone is actually on it painting. And it’s Kenny Scharf. I’ve known Kenny for years and it was a magical New York moment. It’s snowing, no one is on the streets. There’s Kenny. I stand below and he looks down just as I look up and he knows we know each other. And so I felt like that’s kind of how New York was. And I miss that. I miss Andy giving away Interview Magazine uptown. Or coming to Fiorucci and [ Warhol’s assistant ] Benjamin Liu and whoever else are going out to a night at Area with Jean-Michel [ Basquiat ]. I see Andre Serrano around and we are friendly.

stated: You’d be enjoying it a lot more if it were continuing to happen. If there were still people to be inspired by.

Patrick: If there were new ones. Where are they?

Molua: I feel sorry for kids that are coming here and they can’t have these experiences. I recall when it started to rain one day and I spy a few feet away Andy Warhol, and his wig started to get a little damp and a cab stopped for me. I said to Andy, “You take it, you’ve given me so much, the least I can do is give you a taxi.” He said, “Thank you so much.” But, you know, that experience where you could speak to your heroes—it’s probably a bad thing for any of us to have heroes—but everything was available to people, and we could get that stimulation. It’s really about a kind of stimulation that’s currently missing. If you can talk to your heroes and interact with them it gives you that courage; you feel brave.

Patrick: It’s certainly something to aspire to. Seeing these people wherever you go. And that’s different now. The segregation. They’re not mixing. You know, at Studio 54, Steve’s concept was NOT to segregate people. His concept was to mix everyone together. And he limited it because he had to. But his concept was to mix me, someone from the East Village, Bianca, Mick, Readout, whoever was coming into town, together. That was his concept, and it was a good concept. People say, “Well, he created the velvet rope where people couldn’t get in.” That wasn’t it at all. It was just to limit the push and the crowd. They did choose. But they didn’t choose like they choose now just the one type. I wasn’t just like, “Oh, you are a fabulous multi-millionaire investment banker…you come in. Oh, you’re a freak from the East Village with makeup on, you stay out.” It’s that way now, it wasn’t then.

Molua: That’s when New York is at its best. When people from so many different walks of life come together and that’s one of the big draws. That you are going to be mixing with people from everywhere and the really clever, creative people put together these exquisitely balanced get-togethers. You’d have the Park Avenue lady, the foreign diplomat, the club kid, the painter…

Patrick: It’s like the song, “Native New Yorker.” Up in Harlem, and down on Broadway!

Molua: Exactly!

Patrick: It is! It’s wherever you want it to be, and all together.

—-

“The Dandy’s New York” exhibition is on display at the Dorian Grey Gallery through March 4.

Jackie Rampoldi

Jackie Rampoldi

Reader Comments